Risk Tip #5 – Hungry to understand risk appetite?

I have watched with significant interest and with quiet amusement over the last few years, at the rise and rise of risk appetite. The emphasis on risk appetite in on-line risk forums would lead you to believe that without risk appetite being defined, it is impossible to manage risk.

Most guidelines and standards for risk management highlight the need for organisations to define their risk appetite, risk tolerance and (to a lesser degree) risk attitude. With such importance placed on this requirement to define them, it is reasonable to assume that ISO 31000 – Risk Management – Guidelines and Principles would contain clear and definitive definitions. So, off I headed to the Standard. To say that I was still unclear as to the definition of these terms is an understatement.

You be the judge:

- Risk Attitude. Organisation’s approach to assess and eventually pursue, retain, take or turn away from risk

- Risk Appetite. Amount and type of risk that an organisation is willing to pursue or retain

- Risk Tolerance. Organisation’s or stakeholder’s readiness to bear the risk after risk treatment in order to achieve its objectives

The Institute of Risk Management defines risk appetite as: the amount and type of risk that an organisation is willing to take in order to meet their strategic objectives.

All of these definitions differ, however, in simple terms they are pretty much saying the same thing: how much risk am I willing to take to achieve what I need?

So how do we define our risk appetite? Before I answer that question, it is important to first understand why we need to define it.

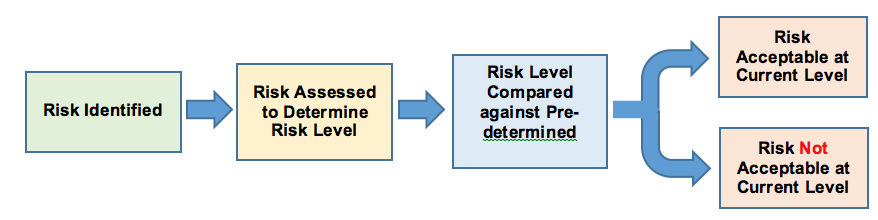

In my opinion, there is one purpose only for defining a risk appetite and that is to articulate the level of risk an organisation is willing to accept. In simple terms, what we need is a methodology/criteria against which we can compare the assessed level of an identified risk to determine if it is acceptable or unacceptable in its current form (i.e. at the assessed level). Diagrammatically it looks like this:

If we accept that having a risk appetite helps us to determine whether an assessed risk is acceptable or not, we can then test a range of methodologies for describing/defining risk appetite to work out whether they lead to the required outcome. Here’s an example:

| Risk Name: Test Risk | ||

| Likelihood Rating | Possible | |

|

Consequence Ratings |

Financial | Minor |

| Reputation | Moderate | |

| Safety | Minor | |

| Compliance | Minor | |

| Risk Level | Medium | |

So, let’s start comparing.

Some organisations opt to take a broad approach to define their risk appetite:

- Averse:Avoidance of risk and uncertainty is a key organisation objective.

- Minimal:Preference for ultra-safe options that are low risk and only have a potential for limited reward.

- Cautious:Preference for safe options that have a low degree of risk and may only have limited potential for reward.

- Open:Willing to consider all potential options and choose the one most likely to result in successful delivery, while also providing an acceptable level of reward and value for money.

- Hungry:Eager to be innovative and to choose options offering potentially higher business rewards, despite greater inherent risk.

These statements are very unhelpful when it comes to determining if a risk is acceptable or not.

Effective at determining whether a risk is acceptable or not?

An increasingly popular approach is for organisations to try to capture Risk Appetite Statements. For example:

- XYZ has zero tolerance for incidents resulting in death, or serious injury or adverse health outcome for customers as a result of an act, or failure to act, by XYZ which can influence the outcome.

- XYZ has a limited appetite for unintentional loss of customers due to customer dissatisfaction in existing business segments. XYZ has a limited appetite for occupancy rate variances to budget.

- XYZ has zero tolerance for a breach of its code of conduct by employees and volunteers.

- XYZ has no appetite for voluntary staff turnover ahead of industry average for six months without a formal treatment plan.

- XYZ has an appetite for formal succession plans with nominated successors for key Executive roles, the Board and Management roles.

To be brutally frank, I have absolutely no idea of the purpose of such statements. Understanding that an organisation has zero tolerance for breaches of its code of conduct does not help us to determine if a risk is acceptable or not.

Effective at determining whether a risk is acceptable or not?

Risk Appetite Diagram

Recently I have also seen risk appetite being captured diagrammatically as shown below:

In fact, this approach is captured in an information sheet issued by a leading Commonwealth agency to demonstrate how to define risk appetite.

In this example, the risk profile is defined as an organisation’s entire risk landscape reflecting the nature and scale of its risk exposures aggregated within and across each relevant risk category.

In my opinion, this almost treats the risks within the organisation as being akin to a bucket of risk where you want to be not too full or not too empty. But how do you establish the risk profile? Is it based on risk level or is it based on consequence? How do you define it? Is it based on financial impacts, reputation impacts, compliance impacts? What are the corrective actions that are available if it does exceed limits?

In addition, this diagram is suggesting that if the profile exceeds capacity the organisation is unviable. That would be true if all of the risks occurred at the same time and became issues – but the fundamental tenet of a risk is that it is not certain to happen.

Effective at determining whether a risk is acceptable or not?

Evaluation Criteria

The methodology I was introduced to first in terms of determining whether a risk is at an acceptable level or not was the use of a table similar to the one shown below:

| Risk Level | Risk Acceptability |

| Extreme | The impact of this risk occurring would be so severe that the related activity would need to cease immediately. Extreme risks need immediate migration strategies to be implemented. |

| High | This type of risk cannot be accepted. Treatment strategies aimed at reducing the risk level should be developed and implemented as soon as possible. |

| Medium | This level os risk can be accepted if there are no treatment strategies that can be easily and economically implemented. The risk must be regularly monitored to ensure that any chance in circumstances is detected and acted upon appropriately. |

| Low | This level of risk can be accepted if there are no treatment strategies that can be easily and economically implemented. The risk must be periodically monitored however to ensure that any change in circumstances is detected and acted upon appropriately. |

This is a very simple approach that tells us the levels of risk we are willing to accept or not accept.

Ability to determine whether a risk is acceptable or not?

but ……….

This approach treats all risks as equal in terms of acceptability – but they are not.

So, what are our options in terms of gaining an understanding of what risks are acceptable and those that are not – our risk appetite so to speak.

The Target Level of Risk Approach

Personally, I do not use the term risk appetite, preferring instead to use the term target level of risk. In addition, I do not treat all risks as equal.

Let’s say we have two risks:

Risk 1 |

Risk 2 |

||||

| Likelihood Rating | Possible | Likelihood Rating | Possible | ||

|

Consequence Ratings |

Safety | Minor | Consequence Ratings | Safety | Minor |

| Security | Insignificant | Security | Insignificant | ||

| Quality of Services | Insignificant | Quality of Services | Insignificant | ||

| Financial | Moderate | Financial | Minor | ||

| Legislative Compliance | Minor | Legislative Compliance | Minor | ||

| Environment | Minor | Environment | Minor | ||

| Reputation | Minor | Reputation | Moderate | ||

| Risk Level | Medium | Risk Level | Medium | ||

Both the risks have the same likelihood and consequence and have the same risk level – Medium. But in the first example we can see that the highest level consequence is the financial consequence and in the second example the highest level consequence is against reputation.

If we were to use the table in the previous section, we would view both of these risks as being the same and will probably accept both of them. But do we have a different appetite for risks with higher safety consequences than we do for those with financial consequences.

This question led me to develop the following target level of risk matrix:

| What is our target level of risk against each impact category? | ||||

| Impact Category | Low | Medium | High | Extreme |

| Safety | ♦ | |||

| Security | ♦ | |||

| Quality of Services | ♦ | |||

| Financial | ♦ | |||

| Legistlative Compliance | ♦ | |||

| Environment | ♦ | |||

| Reputation | ♦ | |||

This table tells us that Risk 1 is at our target level of risk (Medium) and so there is no requirement to develop further controls/treatments. Risk 2, however, exceeds the target level of risk (Low) for Reputation, so in this case, the risk needs to be considered for potential additional controls/treatments.

This is a very simple approach, however, reduces significant confusion to those undertaking risk assessments within the organisation. More importantly, however, it takes risk appetite away from being theoretical to something practical.

That’s all for this risk tip. I look forward to sharing another one with you for my bumper 10th Anniversary Newsletter in May.