Victoria’s Coronavirus 2nd Wave through the Lens of the Swiss Cheese Model

Right now, Victoria is in the grip of a second wave of COVID-19 and to date, it has accounted for approximately 80% of all deaths recorded in Australia during the pandemic, with the majority of those deaths during this second wave.

As cases continued to rise, concerns began to be raised that the hotel quarantine program for returning travellers established by the State Government was the culprit.

The program, and potentially what went wrong, is the subject of an inquiry that, I believe, will find numerous failings that, perhaps could and should have been avoided. This blog does not point the finger at one organisation. The emergence of the second wave of the outbreak in Victoria is characteristic of all failures such as this – it is a system failure.

This blog will shine a light on some of these potential failings through the lens of James Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model.

I do need to state at the outset that there is no suggestion that the issues identified within this blog apply to all the security companies or subcontractors. Any companies listed within the blog are drawn from media reports that are in the public domain.

The Swiss Cheese Model

The Swiss cheese model of accident causation is a model used in risk analysis and risk management, including aviation safety, engineering, healthcare, and emergency service organisations.

The model likens control systems within an organisation to multiple slices of Swiss cheese, in which the likelihood of a risk becoming a reality is mitigated by the differing controls which are “layered” behind each other. In theory, lapses, and weaknesses in one defence do not result in the materialisation of the risk, since other defences also exist, to prevent a single point of failure.

When the holes in the Swiss cheese align that is when the incident occurs (i.e the risk materialises). The aim of managing risk, therefore, is to reduce the number and/or the size of the holes in the Swiss cheese to reduce the chance of alignment.

The Risk

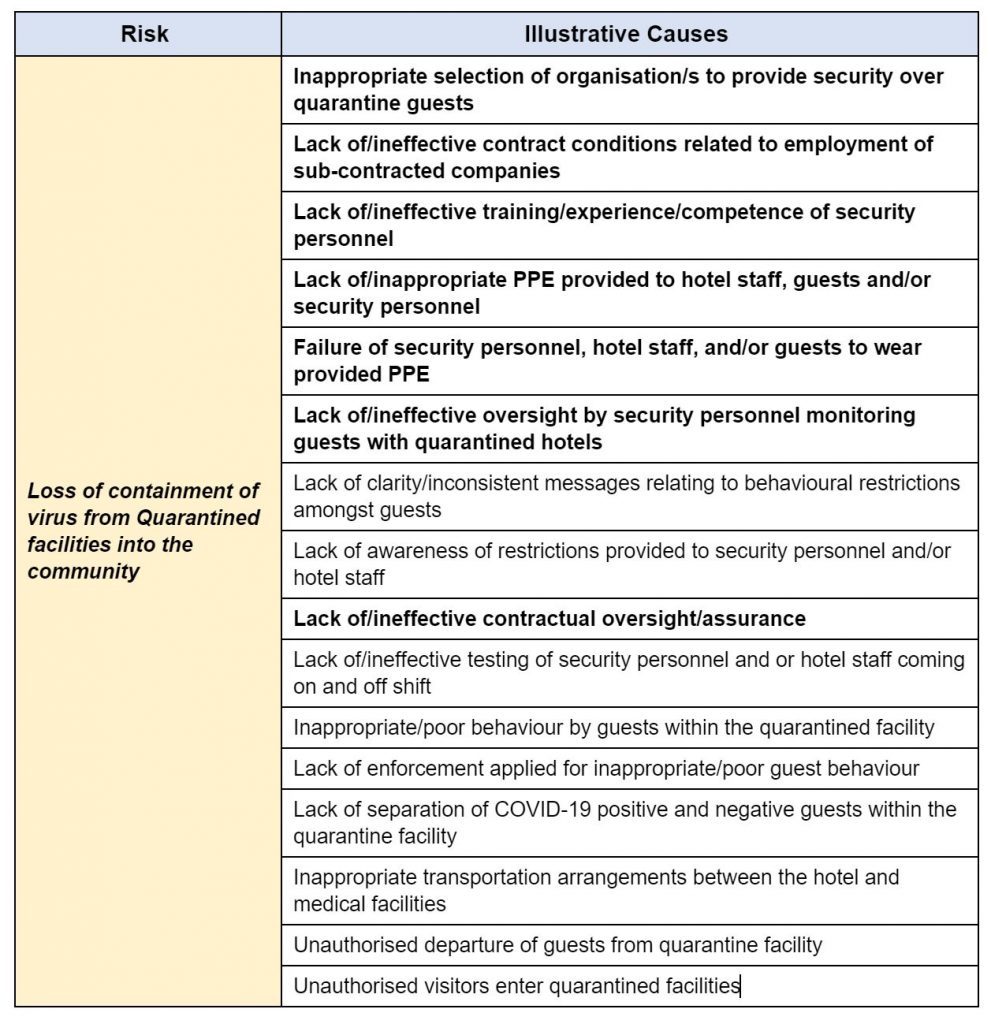

It is important to note that there were a number of risks associated with the program, however, I will just focus on the primary one, which I believe should have been identified:

Loss of containment of virus from Quarantined facilities

So, let us start with the causes (although there are more):

I will now look at some of these causes (highlighted) in more depth, and in light of what we now know.

Inappropriate selection of organisation/s to provide security over quarantine guests

This cause has been the subject of much conjecture and, during the inquiry, the source of, as described by the ABC a swirl of “duelling statements”, claims and counterclaims.

In most other jurisdictions, the security at quarantine facilities was provided by Police, with, in some cases, assistance from Defence personnel. That, of course, is not the only alternative, however, when considering the options for the security and oversight of guests in these facilities, it is important to consider the level of authority required in order to enforce the restrictions placed on the guests – authority that the Police have – authority that security guards did not.

This is not to say the services cannot be provided by personnel without authority, however, if they are, it is essential that there is a constant presence at the hotels by an organisation/s that do. (i.e. Police).

Commercial security companies were engaged and expected to enforce the restrictions placed on those in hotel quarantine with no authority. That is all well and good if guests behave in accordance with those restrictions, something we now know not to be the case.

In my view, this was not a case of multiple “holes” in the slice of cheese (the control), this was one massive “hole” that could impact the whole of the program, regardless of the contractual performance of individual security companies (unless additional controls were added – which appear not to have been the case).

Lack of/ineffective contract conditions relating to employment of sub-contracted companies

What we now know is that the contract did allow for the engagement of sub-contracted companies.

In fact, one of the companies hired five subcontracted companies to provide the services. That company ended up overseeing security at 13 hotels and stated that it required all sub-contractors to comply with industrial obligations and conduct audits to ensure correct payments to staff. [The Age, 24 July]

Another of the companies engaged by the Victorian Government, failed to inform at least one of its subcontractors of its obligations. As reported by the ABC the cover up was disturbing:

Wilson Security then attempted to conceal this failing by asking the subcontractor to backdate documents for the Government.

Wilson made the backdating request in an email, provided to 7.30, nine weeks after its subcontractor had hired guards to work in a quarantine hotel.

But, herein lies one of the most basic and fundamental issues with contract management: it is the contracting organisation’s obligation (the Department) to assure that the lead/head contractor is meeting all of their obligations, and the responsibility of the lead/head contractor to assure that the subcontractors are meeting their obligations. Simply assuming they are because there is a contract is as naïve as it is dangerous.

In this case, it could be assumed that there would be companies meeting their contractual obligations, and others that would not. This means that there may have been multiple holes of differing sizes, particularly if there was additional subcontracting by the subcontracted companies.

Lack of/ineffective training/experience/competence of security personnel

What we also now know thanks to the inquiry, that many of the security personnel were hired over messaging platforms such as WhatsApp; had very little training (if any) and were given very little understanding of their roles and responsibilities.

As one guard, who quit after one shift at a quarantine hotel, highlighted to the ABC’s Four Corners Program:

I received no infection-control training before being posted in a corridor on an upper level of the hotel and was told to stop returned travellers from leaving their rooms.

“All I know about COVID is from television, not from the security company. No training whatsoever,” he said.

It is widely accepted that the security industry is characterised by a workforce that is highly casual, relatively low-paid and transient – not exactly conditions that would inspire confidence that the level of conscientiousness is going to be consistent across the entire workforce hired to oversee the quarantine program. Add to that the lack of authority, and the conditions required for the loss of containment are starting to align.

Once again, with this control, there may have been companies doing the right thing, which means that there may have been multiple holes of differing sizes, particularly if there was subcontracting by the subcontracted companies.

Lack of/inappropriate PPE provided to hotel staff, guests and/or security personnel

The provision of appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) to guards, staff and guests appears to be an area of conjecture. The security companies maintain that appropriate PPE was provided as well as training in its use, however, this has been widely disputed by personnel engaged to work in the hotels.

At best, the provision of appropriate PPE was inconsistent, which was enough for issues to arise.

This is another control where some companies may have been complying, which, once again, means that there would be multiple holes of differing sizes, particularly if there was subcontracting by the subcontracted companies.

Failure of security personnel, hotel staff, and/or guests to wear provided PPE

The provision of PPE is one thing, the wearing of it is another.

As one of the guards informed The Age:

“I was hired one night before when quarantine starts in hotels. All guards who worked in these hotels didn’t have proper PPE [personal protective equipment] training, no induction, nothing,” he said.

“Security guards used to eat together and hug each other. When I start working in Rydges on Swanston, I didn’t know that all the guests living in rooms are confirmed COVID patients. Guards were instructed to take these people for walks on the rooftop walking area and guards just wear a mask and share lifts with these people.”

In addition, it has also been reported that guests often did not wear their PPE when around guards, other guests and/or hotel staff.

Once again, this control would be characterised by multiple holes of differing sizes.

Lack of/ineffective oversight by security personnel monitoring guests with quarantined hotels

As reported on ABC’s Four Corners program and in the widespread media, images were taken of guards sleeping on the job.

Others fraternised with guests and, in some cases, there was intimate physical contact between guards and guests.

So, we now have another control with multiple holes.

Lack of/ineffective command, control, and/or contractual oversight/ assurance

The lack of understanding of command and control of the program has been highlighted by the fact that the inquiry examining what went wrong in the hotel quarantine program has named six hotels, 10 state government agencies and eight security companies as being “of interest”.

The most damning thing to come out during the inquiry came from the Premier himself:

Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews has conceded it is not clear which department was in charge of the hotel quarantine operation. However, DHHS placed an “authorised officer” in each hotel and was responsible for overseeing infection control.

Given the Victorian Government’s decision to engage private security forms in lieu of the Police or Defence personnel, it was essential that the task of contract oversight and assurance be articulated, and authority given for rectification of any issues/breaches as they arose.

The “authorised officer” may have been responsible for overseeing infection control, however:

- Was there an “authorised officer” present 24/7?

- Did the “authorised officer” have the authority to rectify contract issues, or was this even in their remit?

- What level of experience did the “authorised officers” have in “infection control”?

The lack of understanding as to who was responsible for what would, in my opinion, impact the entire program and, as such, would represent a significant “hole” in the Swiss cheese.

When coupled with the first cause, where the size of the “hole” in that particular piece of cheese could have been greatly reduced had this control been stronger, we are now sailing into extremely dangerous waters.

Conclusion

I could go through a raft of other issues such as:

- Hotel guests requiring medical treatment being transferred in an ambulance but having to find their own way back to the hotels themselves, which would involve either a taxi, an Uber thus increasing the potential for community transmission; or

- Guards working at multiple locations;

- Language issues;

- Multiple guards travelling to the hotels in the same vehicle;

- Guards leaving the hotel on their break to local shops;

but, given the “holes” already identified, it is clear that this was a risk that was almost certain given the arrangements put in place at the commencement.

The use of private security firms did not make what has happened inevitable, however, for the risk to be brought to an acceptable level of likelihood, other controls needed to be significantly more effective than what we now know to be the case.

The arrangements established for this program fell well short of that, and the consequences have been dire. It remains to be seen when the 2nd wave will be brought under control any time soon – but we can only hope.